Telegraph #1

Telegraph #2

Telegraph #3

Telegraph #4

Telegraph #5

Telegraph #6

Mustn't grumble, eh?

ENSCONCED at a corner table of Café Flo in Belsize Park, one leg out and shoulder hunched in a manner that disguised the crippling impairment of the right side of his body, Ian Dury cheerfully explained why he missed our previous appointment the week before. "I 'ad a strange lack of breath," he said, speaking in that impressively deliberate London manner (like Michael Caine reading Shakespeare) that has made him such a staple of advertising voice-overs.

"I'm normally quite fit, but I went up a few stairs at my house in Hampstead and I was gasping like an old geezer. So I went to see my doctor. He gave me an X-ray and a blood test and an ECG, then he told me to wait and he ran out of the building! I thought, bloody 'ell, is it that bad? He thought I was having a heart attack, and he's run next door to the surgeon."

Dury chuckled, before proceeding to describe, in great detail, with many humorous asides, his subsequent hospitalisation. His heart, apparently, was pounding away at an excessive 158bpm. "I was under examination for the whole day in this progressive care unit. There's bleepers going off the whole time. The nurse says, 'Don't look, it'll just make your heart faster!' " The next day, he received mild electric-shock treatment. "It's bang on tempo, 75bpm now. I had an ECG two nights ago and from every angle it's solid, so it's not heart disease." Dury paused, with the timing of an old trouper. "So I'm back on the cancer now, thank God!" he laughed.

Any list of reasons to be cheerful about British music of the last three decades would have to include Dury, whose always witty, usually exuberant and sometimes moving amalgamation of music hall and rock 'n' roll have made him one of the most unusual and inspirational figures in pop.

Yet you might not think that the composer of Reasons to Be Cheerful has had too many reasons himself of late. Having spectacularly triumphed over disabilities left by a childhood bout with polio, he has recently fallen under the shadow of the big C. His first wife, Betty (mother of his two twenty-something children, Baxter and Jemima), died of cancer four years ago. Dury got married again (to Sophy Tilson, 23 years his junior) and started a new family (they have two infant sons), only to be diagnosed with cancer himself. In 1996 he underwent an operation which it was hoped had successfully dealt with cancer of the colon, but last year secondary tumours appeared on his liver.

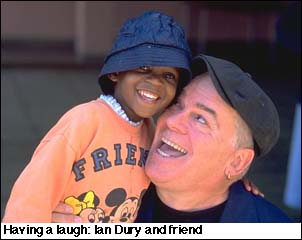

Yet Dury does not come across as a man with weighty issues on his mind. A bright, charismatic character, his conversation fairly sparkles with anecdotes, jokes and witty insights. Unusually for a star, he appears as interested in those around him (from the photographer to the waiter and, indeed, his interviewer) as they are in him. He addresses serious issues seriously (and has much to say about the disparity between the private health care he can afford and that available on the National Health), but displays an inner ebullience that serves to lighten even the heaviest of topics.

This spirit is on full display on his new album, named (with characteristic disregard for notions of decorum) Mr Love Pants. Reunited on disc with the Blockheads (and, in particular, songwriting partner Chaz Jankel) for the first time since 1980, Dury fairly sparkles with the lyrical wit and musical flair that first brought him to the public's attention. A song about the failures of state education (Jack Shit George) nestles comfortably alongside an ode to a sandwich-maker (Geraldine) that appears to exist for the simple pleasure of rhyming "inamorata" with a very cockney delivery of "dried tomato".

"It's not tinged by illness," Dury insisted, explaining that the album's genesis preceded his diagnosis. He is not exactly a prolific lyric writer. A creative reunion with the Blockheads had been on the cards since they started doing occasional gigs together again in the early Nineties, but it took Dury several years to get the material together. Although contrasting notions of living life to the full are explored on Cacka Boom, Bed o Roses and Heavy Living, only one song, The Passing Show, deals with mortality, concluding: "When we're torn from mortal coil / We leave behind a counterfoil."

"Your counterfoil is who you know and what you do," explained Dury, arguing, perhaps disingenuously, that to make a cheque-book reference regarding death was just as "trite" as his inventive sandwich rhymes. "It's a little concept, a little something for the pot. It's nothing profound." But then he added, tellingly: "Despair is private. And despair and grief, they're hinted at, they're alluded to, but they don't consume the project. If they did it would just be so distressing."

Dury, who studied painting at the Royal Academy and taught at Canterbury College of Art, insists he never took his musical career very seriously. "If you're a jazz lover, which I am, you don't think of rock 'n' roll as something to aspire to; you think of it as something you can do quite easily. You don't think you're Rembrandt."

Yet his 1977 solo debut, New Boots and Panties, remains an enduring work, and in a brief period of genuine pop stardom he and Jankel were responsible for a surprising number of classic recordings, including Sex and Drugs and Rock and Roll, Sweet Gene Vincent, Wake Up and Make Love With Me and the number one, Hit Me With Your Rhythm Stick. Dury, however, found fame oppressive.

"I got seriously fed up with being recognised. 'Cause the way I walk, I'm ultimately very recognisable anyway. And I read once that Paul McCartney, if he's recognised too often, he walks briskly away. But if I do that I fall over!" When the hits stopped coming, he didn't lose sleep. "I was doing it to acquire some premises for a start, then get one for me mum and then get one for me family. So I kept going till I got three houses, and then I didn't really have a reason to go through that absolute lunacy any more."

He wrote songs for the theatre and delved increasingly into acting, although he has rarely taken a leading role. "I do cameos," he explained. "I got offered Richard III in Sheffield about 12 years ago and I phoned my agent, and she said. "Darling, The Telegraph send a man to Sheffield." I think what she meant was, do the little ones and pick it up as you go. I couldn't do Richard III, no way. I didn't go to Rada. The only thing I would bring to it would be authenticity, because I'd be disguising the fact that I was disabled rather than waving it about, which is where they get it wrong."

Ownership of his back catalogue has kept him financially secure but he is clearly enjoying his revived career. "Working is a distraction," he admitted. "I'm not sitting there being morbid and worrying about cancer particularly, but it does take your mind off it." His attitude to his fate is refreshing, if not quite resigned. "My medical advisers are top of the range. So I stopped worrying about me cancer, 'cause if they can't fix it, no one can. So what's the point in getting worried? The prognosis is if it's able to be kept at bay it will be. But it's a wily bastard, cancer."

He spoke movingly of the bravery of the many young men who have died of Aids in the last two decades, and of the letters he has received since speaking out about his illness. Clearly, Dury, the disabled, working-class lad made good, has not lost the ability to count his blessings. "I'm 56. I would be more disgruntled about having cancer if I was 46, or if I hadn't had a good crack, as they say. I've had a good run. Mustn't grumble."

Then, without prompting, he fell into reminiscing about his father. "My old man was 62 when he died. He spent nine hours at Heathrow airport in the rain, smoking too many fags, talking to the other chauffeurs, waiting for his boss to come back from Belgium. And he died that night of emphysema, in a lonely little bedsit up in Victoria. They took him to Caxton Hall Registry, you know, the morgue. And I had to identify his body.

"So there's my old man laying on this purple velvet slate with a lovely stained-glass window with this strange smile. I knew he didn't look quite right. I didn't realise until I cleared his room out that he hadn't got his teeth in. I went and knocked on the bloke next door in the next bedsit, and I said, 'Did you know my dad?' I said, 'Would you mind . . . his shoes and his teeth? I can't handle it. I can't touch 'em.' He got rid of them. Everything else was all right. But I couldn't touch his f*cking teeth."

Dury laughed. And he has such a great laugh that you want to laugh with him. But his eyes were moist as he spoke. "They forgot to put his teeth in," he said. "But ... they can't remember everything, can they?"